For decades, the language around data has barely changed. Every few years a new architecture or philosophy rises. We hear about data lakes, warehouses, meshes, fabrics, and observability platforms. Each is a promise to finally tame the chaos of data management. Billions have been invested across multiple generations of tooling revolutions, yet the core experience remains remarkably constant: Data is hard to find, hard to trust, and harder still to use when it matters.

The remarkably consistent pain under different names suggests that the problem is not one of missing technology but one of misplaced framing. It’s not ignorance or incompetence but a structural mismatch between how data actually behaves and how organizations attempt to control it.

Most data programs are built on an implicit belief: If we can just get data right, if it was standardized, governed, and modeled correctly, then the rest will follow. The logic feels sound. Clean inputs produce reliable outputs. With enough oversight and control, every dataset can be made trustworthy and represents the truth.

This conviction underpins nearly every subdiscipline of data management:

These frames capture something true but partial. Each treats the problem as a deficiency in a single dimension, like technology, policy, or culture. It implies that if repaired, it would unlock the data potential of the enterprise. But the pattern repeats: small local improvements, global stagnation.

Data is inherently cross-cutting. It passes through departments, systems, and time horizons. It is both artifact and process: a record of the past and the basis for future action. This duality makes it resistant to central control.

Organizations, by contrast, are built for focus and autonomy. Functional units are designed to operate within clear boundaries, optimizing for clarity and control. Data, by contrast, moves across those boundaries. It gathers meaning not only within its domain, but also through connection. The result is a structural misalignment between how organizations are arranged and how information must move to be useful.

All attempts to impose strict order eventually run into this contradiction. Centralized data teams become bottlenecks because they sit outside the domains that generate meaning. Federated models fragment because domains rarely have the technical or conceptual capacity to maintain full autonomy.

The system fights itself. Governance adds layers of friction to regain control. Tools proliferate to smooth over the friction. The cycle repeats.

The data industry has achieved astonishing technical feats. Columnar storage, query optimizers, stream processing engines, cloud elasticity, and vectorized computation have expanded what is computationally possible by many orders of magnitude.

However, these advances largely reproduce the same conceptual architecture: Data is extracted, transformed, and loaded into a central repository where it can be analyzed. Every generation rebuilds this pattern with more sophistication, but the underlying assumption is still that utility requires pre-integration and pre-modeling.

The result is a steady improvement in plumbing without a corresponding improvement in adaptability. Systems grow more powerful but also more brittle. The time between a business question and a usable dataset often remains measured in weeks or months. This pattern optimizes for consistency across time rather than responsiveness through time.

Data work exists in two incompatible time domains.

AI accelerates this mismatch exponentially. Training a model requires historical data shaped in ways that didn’t exist when that data was collected. Running inference requires real-time feeds. Each AI experiment demands data in different formats: vectors for RAG, tables for analytics, events for fine-tuning. Traditional pipelines force teams to choose which use case to support, or build three separate flows from the same source.

By the time a pipeline or model is completed, the context that defined it has shifted. What was accurate becomes stale; what was relevant becomes peripheral. The same loop of redesign begins again.

Most thought leadership misidentifies this drift as a tooling or governance gap rather than a fundamental property of how data interacts with human systems. The issue is not that we fail to plan well enough but that plans cannot keep pace with reality.

I believe the industry seems trapped in repetition partly because repetition is profitable.

Every cycle of failure generates new categories. DataOps, observability, data contracts, lineage, semantic layers all become solutions that can be productized and sold. The promise of a definitive fix is an effective business model precisely because the fix never materializes.

I don’t want to suggest bad faith. I believe most people in industry sincerely seek improvement. But the structure of incentives favors perpetual partial solutions over fundamental redesign. A universal framework is easier to market than a context-specific reform of organizational behavior.

Recent movements hint at deeper shifts. “Data as product,” “data contracts,” and “domain ownership” all acknowledge that data cannot be abstracted away from the contexts that produce it. The move toward event-driven and immutable systems acknowledges that the past cannot be rewritten without consequence.

The emergence of AI as a primary consumer of data has made these tensions impossible to ignore. LLMs, RAG systems, and ML models don’t just need clean data. They need replayable data, transformable data, data that can be reshaped for experimentation without months of pipeline work.

Yet, even these trends risk the same cycle if they are treated as doctrines rather than design principles. The main insight that they share is that data systems must align with the natural structure of organizations and the flow of time. This insight requires more than new tools. It requires a change in mental model.

Matterbeam’s work begins from a different premise. The recurring crises of data management are not signs we’ve failed to find the right pipeline pattern or that our people are deficient. They are evidence that pipelines themselves are the wrong abstraction for most organizational data problems.

Pipelines assume that data must be moved, reshaped, and centralized before it can be useful. This produces fragility: Every new use case adds another layer of dependency, every schema change ripples across systems. The effort to achieve consistency consumes and eclipses the capacity for innovation.

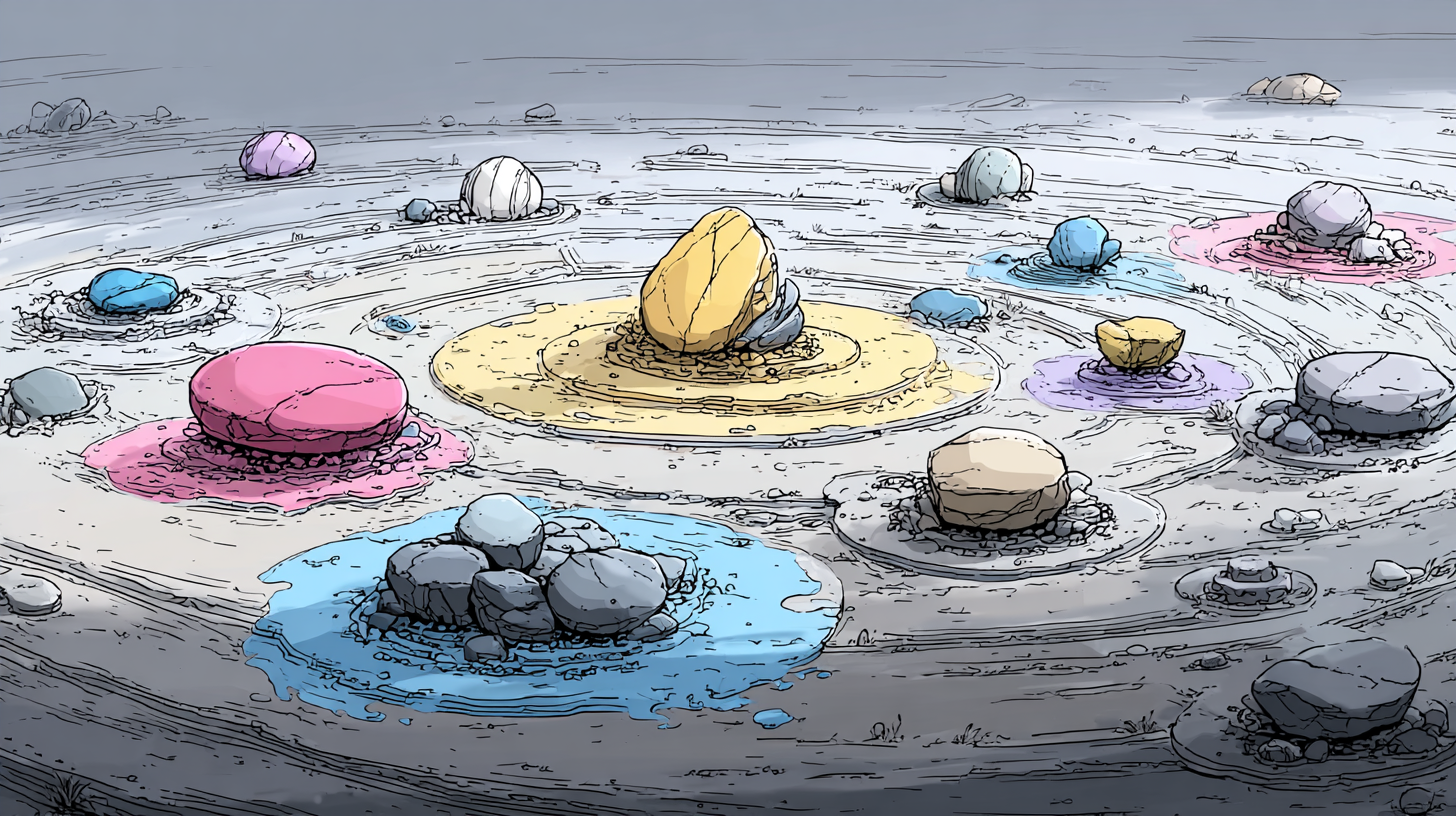

Matterbeam treats data instead as a utility. It’s aiming for a shared foundation that can be tapped, transformed, and recombined without dismantling its history. Rather than constructing and maintaining ever-more complex flows, Matterbeam stores data as immutable fact streams. Each fact represents an event in time. Transformations are applied on demand, producing derived views without altering the source.

This architecture changes where control lives. Instead of forcing the world to conform to a canonical model before data can be used, it preserves the raw semantics of events and allows interpretations to evolve. Change becomes a first-class citizen rather than a threat.

Traditional architectures try to create order with centralization: a single warehouse, a single model, a single governance layer. But order can also emerge from composability with the ability to build complex systems from simple, self-contained parts.

In Matterbeam’s approach, every dataset is derived through explicit, reversible transformations. Each step is observable, testable, and replayable. The result is not a static model but a living graph of dependencies. Teams can iterate locally without jeopardizing global integrity because every operation is a function of immutable inputs.

This matters acutely for AI work. A data scientist testing embeddings for RAG needs the same source data as the analyst building dashboards and the engineer feeding production models. Traditional architectures require three separate pipelines. Immutable streams and on-demand transformation create three views of the same foundation: each testable, replayable, and independent.

This design reintroduces the time dimension that most data systems flatten or discard. Historical state is preserved, not overwritten. Analyses can be recomputed for any point in time, allowing systems to reason not only about what is true, but when it became true. It allows systems to create alternate interpretations in parallel.

The practical implication of immutability and composition is not merely reliability but organizational elasticity. When data is replayed, reshaped, or reinterpreted without rebuilding pipelines, teams gain freedom to explore. The cost of change and iteration, the real tax that constrains innovation, drops dramatically.

This matters because most data teams are not paralyzed by a lack of insight but by the fear of breakage. Every modification risks disrupting dozens of dependent systems. As a result, small analytical questions turn into engineering projects. Ad hoc requests are ignored or derided. New use cases are marginalized. The promise of agility collapses under the weight of accumulated coupling.

Matterbeam’s philosophy is an attempt to reverse that gravity. Treating every piece of data as a stable reference point and every transformation as able to be recomputed, decouples exploration from maintenance. The organization can evolve its understanding of the world without rewriting its past.

The persistence of data problems is often interpreted as evidence that we have not yet found the right framework. But it may be evidence that the pursuit of a single framework is itself the problem. Data exists at the boundary between systems that cannot be unified this way: technical and human, formal and tacit, stable and fluid.

What matters is not eliminating these tensions but designing architectures that can absorb and express them. Immutability, replay, and on-demand transformation are mechanisms for doing exactly that. They do not simplify the world by ignoring change; they simplify the work by making change tractable.

This perspective reframes governance and quality. Instead of attempting to enforce correctness at the point of ingestion, or correctness at the point of central storage, correctness becomes a property of interpretation. Each derived view can be validated, audited, and versioned independently. Governance becomes compositional rather than monolithic.

An honest engagement with the history of data management suggests that progress will not come from discovering the next revolutionary model but from building more honest infrastructure. We need systems that reflect how organizations actually evolve rather than how we wish they behaved.

Matterbeam’s aim is not to declare the end of data problems but to re-align the foundation and tracks on which those problems occur. Separating facts from interpretations and enabling reversible computation creates conditions where failure is local, recovery is trivial, and experimentation is safe.

In this sense, Matterbeam is less a product than a correction, a reassertion that data infrastructure should make information usefully imperfect in the moment it’s needed, not perfect it.

If there is a lesson in decades of circular progress, it may be that the rhetoric of mastery has reached its limit. Data will never be fully controlled, fully clean, or fully democratized. It’s a living artifact of human systems, and human systems are noisy. The task ahead is not to eliminate that noise but to build infrastructures capable of surviving it. Systems that acknowledge change as the default state and allow understanding to keep pace.

Matterbeam’s architecture embodies that acceptance. It treats every fact as both permanent and provisional: permanent in record, provisional in meaning. From that foundation, the endless cycle of new doctrines begins to look unnecessary. We may not need another “modern data stack.” We may simply need to stop erasing the past every time we try to improve it.

Want to see how immutable streams change AI velocity? Talk to a Matterbeam engineer.